St. Kilda

Borerary appears centre-frame in the distance.

Nikon D810 24-70mm f2.8 at 70mm. 1/2000sec f7.1 ISO 200

The sun shone warmly as we bounced across a ten-foot North Atlantic swell at 26 knots heading into 20mph winds. I was relieved our boat had departed at all, the previous five days sailings having been cancelled due to inclement weather. Despite standing on the exposed rear deck of the RIB, I was overheating inside two layers of fleecy, windstopper clothing and a heavily quilted camouflaged jacket. I was unconvinced that we would make landfall with my breakfast still in place!

I will never know whether it was the gin gin ginger-flavoured candy sweets or sheer willpower, but nearly five hours after departing Uig on Skye, I made it to the harbour landing steps in one piece. All feelings of nausea immediately subsided to be replaced by a feeling of awe at my home for the next few days. My good friend Tim and I were on the Island of Hirta, the largest of the St Kilda archipelago.

Dun.

Nikon D810 14-24mm f2.8 at 14mm. 1/2500sec f8 ISO 64

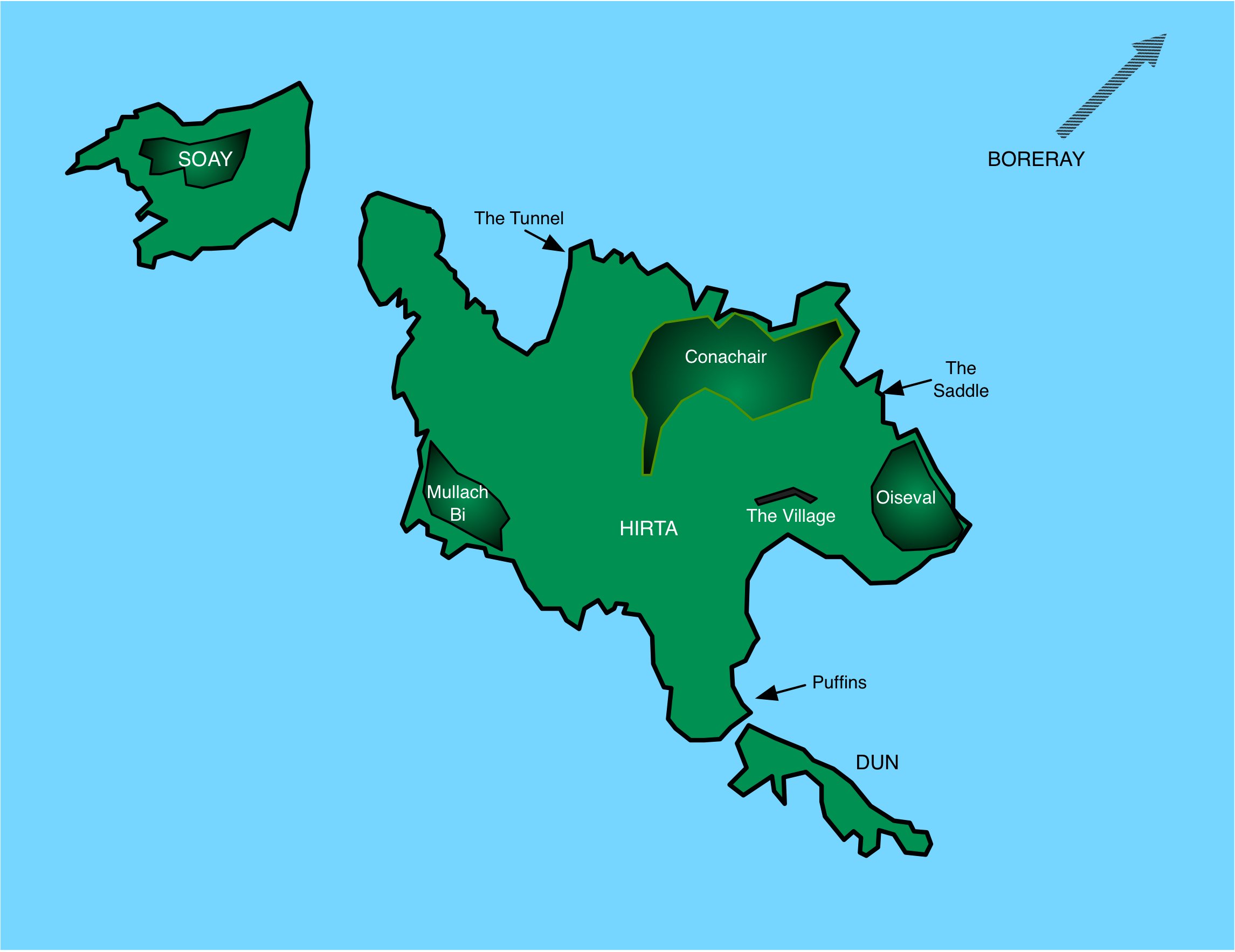

St Kilda is a long extinct volcano comprising four islands, Hirta; Dun; Soay and Boreray. It sits on the edge of the European continental shelf, about 40 miles west of the nearest landmass on Scotland’s Outer Hebrides. It holds the status of UNESCO dual World Heritage Site both for its exceptional cultural history and biodiversity, one of only 35 locations in the world and the only one in the UK to do so. In the winter months the islands are mostly deserted, occupied by a handful of military contractors. During the summer, apart from day-trippers and the odd camper, the island is additionally home to a handful of people managing the island’s ecosystem or conducting research. More importantly, the human inhabitants are joined by one of the world’s largest gatherings of seabirds including puffins; guillemots; gannets; fulmar; razorbills and kittiwakes.

Village Bay, Hirta. Conachair on the left, Oiseval on the right.

Nikon D810 14-24mm f2.8 at 14mm. 1/320sec f8 ISO 64

Main Street, Hirta.

Nikon D500 24-70mm f2.8 at 24mm. 1/160sec f8 ISO 8

I have always been fascinated by stories of St Kilda and longed to visit for many years. I came equipped with a large bag of camera gear, camping equipment and enough food for ten days in case we became stranded by poor weather. Apart from the usual attempts to build my photographic portfolio, I had considered extending my tour operations to this unique location, so this trip also served the purpose of reconnaissance.

I carried the following photographic gear:

Gitzo Systematic tripod and monopod with ball head

Nikon cameras: D810 and D500

Nikkor lenses: 14-24mm f2.8; 24-70mm f2.8; 70-200 f2.8; 300mm f4 and 500mm f4

Nikon teleconverters TC20 III and TC14 II

Nikon SB800 speedlight

Lumix GM5 with 12-32mm f3.5-5.6

Map of St Kilda

St Kilda offers no access to electricity for charging camera batteries or phones; no cellphone coverage; and nowhere to purchase food supplies. Therefore, everything needs to be carried. Thankfully, it is only a few hundred metres from the jetty to the camping area.

Apart from the immediate vicinity of the military base and ruins of the village, the land is steep everywhere. Behind the ampitheatre of grassy slopes, the ground falls away precipitously to the sea, many hundred metres below. Although this was midsummer, St Kilda is notorious for its exposure to severe weather fronts experiencing storm force winds seventy days a year and has twice the summer rainfall of Edinburgh. I was surprised therefore to be experiencing a heatwave during the four days of our stay. Carrying heavy photographic equipment to locations across the island in these conditions was an unexpected challenge.

On the first morning I set off about 3.50am to the saddle between Conachair and Oiseval. I was equipped with both the D810 with 70-210mm and D500 fitted to my 500mm carried in Think Tank holster and Glass Limo respectively. My Gitzo Systematic tripod with ball head was strapped awkwardly to the Glass Limo.

Stac Lee.

Nikon D500 500mm f4. 1/1000sec f7.1 ISO 100

Fulmar Chick.

Nikon D500 500mm f4. 1/800sec f10 ISO 1000

From this vantage point, I had a stunning view across four miles of ocean to the island of Boreray and the colossal sea stacks of Stac Lee and Stac an Armin. A burning orange sunrise emerged from the horizon beyond. On the sea cliffs of Conachair, the largest in the UK, I could see dozens of fulmar gliding in turns along the cliff’s edge, using the updraft for added propulsion. Some nested on narrow ledges and a few unattended youngsters waiting patiently for a parent to return with food.

I used the D810 and 70-200mm lens combination to capture a range of combined wildlife and landscape shots as the sun rose. I used the camera in manual mode with matrix metering. The photograph of the young chick on the grassy ledge was captured with the D500 and 500mm f4 combination.

During the morning, I proceeded over the summit of Conachair, visiting various lofty viewpoints along the way. By now, my good friend Tim had relieved me from carrying the aforementioned Gitzo tripod.. and will hereafter, forever be known as Timmy the Tripod! That afternoon I dropped down to The Tunnel at Glen Bay to find guillemots. My descent into the Glen was resisted by repeated raids from great skuas. They nest in numbers in this valley and attack any creature venturing near the cleits where they conceal their young chicks. I had been advised that attacks were best repelled by positioning one's extended walking pole above the head. Nonetheless, the birds like determined fighter pilots, attacked from our blind-side and zipped past within a few inches, beaks ferociously agape. Although I was not actually struck, these large birds fly remarkably close and had it not been for the ‘pole’ advice, I feel certain I would have been hit.

Guillemots and Razorbills nesting on a cliff ledge near the Tunnel.

Nikon D500 70-200mm f2.8 at 200mm. 1/1250sec f3.5 ISO 140

Great Skua.

Nikon D500 500mm f4. 1/1000 f7.1 ISO 450

The Tunnel is a natural tunnel eroded through a short, rocky, narrow peninsular by the action of the sea. At some point in time the bridge will collapse and a new sea stack will be born. It was here that I saw my first guillemots and razorbills in any numbers but unfortunately the numbers were small and they were also some distance from my position. Even the 500mm lens was unable to achieve much more than contextual shots.

The following day we repeated the sunrise visit to the saddle, this time equipped with just the D810 and 24-70mm lens. The sunrise was yet more impressive and the wind had risen significantly, creating a heavier updraft and providing an improved opportunity to capture the fulmars gliding and on this occasion, hovering in the air current.

Nikon D500 500mm f4. 1/2000sec f4 ISO 180

Later that morning I crossed to Mullach Bi where, far below on the steep cliffs, I could see hundreds of puffins like tiny specs, darting about amongst the rocks. Much closer, however, were fulmar chicks, again perched home-alone amongst the rocks and waiting to be fed. I waited for several hours to see if the parents would return. I had left the D810 back at the tent and was armed, once again with the D500, 500mm lens and tripod. I trained the D500 on the chicks and waited.. and waited.. and waited. Three times my heart missed a beat as adult fulmars landed on the narrow ledge, and three times they paused, looked suspiciously at the foreign chick and left again.

Eventually I moved down to the eastern cliffs on the southernmost tip of Hirta, near the gorge that separates Hirta from Dun. The previous evening I had briefly seen puffins landing here on their way to and from the sea. About 1km distant, huge numbers of puffins, with burrows on the inaccessible island of Dun, could be seen coming and going from the grassy slopes above the sea cliffs.

Nikon D500 70-200mm f2.8 at 200mm. 1/1000sec f6.3 ISO 1600

Small numbers of puffins were, however, briefly congregating again, much as they had on the first evening. To capture shots of the settled birds I used the 500mm lens, alternating between the D810 and D500 depending on how close I was to the birds and the need for the higher burst rate (10 fps) and shot buffer (200) of the D500. For shots of the birds in flight, I used the D500 and 70-200mm combination. This pairing is lighter and can be hand-held with ease, making it easier to get the birds in frame and acquire focus. I always use the autofocus-continuous mode and back-button focusing. In general, I just have one focus point selected.

Nikon D500 70-200mm f2.8 at 200mm. 1/1600sec f6.3 ISO 1600

After four days on the extraordinary island of Hirta a tourist boat collected us for our return journey. Before embarking on the return crossing, we paused opposite Dun; the cliffs at the base of Conachair and then crossed the four miles to the northern gannet colony on Boreray. The latter, with its two towering sea stacks was by far the most impressive wildlife highlight of the journey. Boreray rivals Bass Rock on the Scottish east coast for gannet numbers and is no less dramatic. Photographically, however, it presented a real challenge. The RIB bobbed about on the sea like a cork and the small rear deck was crammed with twelve people vying for position, all of whom, despite my frustration, were just as entitled as I to take photographs.

I carried the D500 fitted and 70-200mm f2.8 lens. This combination provided the best flexibility and again, gave me the impressive burst mode and buffer of the D500. I had the camera in manual exposure mode with matrix metering. I set the shutter speed to 1/2000sec and aperture to f9. When shooting birds against the sky I increased the EV to +0.7 or +1 to maintain shadow detail. Given the circumstances, there was an element of ‘spray and pray’ about my photography and although I got some results, I rightly anticipated a poor keeper rate. I also carried the Lumix GM5, with 12-32mm lens (2x crop factor) for wider shots.

Stac Lee (foreground) and Stac an Armin (background). Stac an Armin is the highest sea stack in the British Isles.

Lumix GM5 12-32mm f3.5-5.6 at 32mm. 1/2500sec f8 ISO 1000

The return to Skye was not without incident but nonetheless, much more comfortable than the outward journey.

Boreray with Dun in the background.

Nikon D500 70-200mm f2.8 at 70mm. 1/2000sec f9 ISO 360

So what of St Kilda? I had read books on this dramatic place many years ago and was well acquainted with its unique and amazing accounts of human occupation in extreme conditions. I had also read about the wildlife and hundreds of thousands of seabirds that I could expect to find there. Given the reported volume of seabirds, I was expecting an experience with an intensity to rival the Farnes in Northumberland or Bass Rock in the Firth of Forth, where the number and proximity of the seabirds is overwhelming. With the exception of the Boreray gannets, I was therefore both surprised and disappointed at the comparatively small numbers I witnessed. I did not see any kittiwakes at all and only very small numbers of razorbills and guillemots. I did not see any puffins carrying sandeels for their young either. Some deeper research on my return uncovered a short National Trust for Scotland documentary (St Kilda: Facing the Change) on YouTube and an article in The Guardian reporting the adverse effect of climate change on fish stocks in the north Atlantic and consequent impact on St Kilda seabird numbers. The kittiwake is all but extinct here and other birds such a puffins are in dramatic decline.

Taking wildlife photographs in any new environment presents a steep learning curve and with hindsight I should perhaps taken advantage of the opportunity to capture images of the skua attack or the unique, endemic creatures such as the St. Kilda field mouse, wren and feral sheep. I was probably too focused on reaching the goal I had set to record the puffins, razorbills and other seabirds.

Leaving St Kilda.

Nikon D500 70-200mm f2.8 at 70mm. 1/2500sec f9 ISO 560

St Kilda is a unique and extraordinary place and I have no regrets making the difficult journey. The scenery is highly dramatic and any landscape photographer would be in their element here. Had my wildlife expectations been more realistic, I would probably have been less disappointed. Nonetheless, the logistical difficulties of getting here and challenges I encountered means I won’t be bringing clients here any time soon.

I visited St Kilda in July 2017.

If you liked this article, please like it and feel free to ask questions or post a comment.

Subscribe to my newsletter at the bottom of the page if you want to follow this series. Alternatively, follow me on Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.